Rye Town Park: How Lucky We Are

As April’s Earth Day celebrations come to a close, we chose to honor the nature and history of Rye Town Park for this month’s Rye Story.

When I came to Rye for the first time in 1995, I was eighteen years old. I spent one night here with my friend Maria’s family on the front end of Spring Break, a stop on the way to JFK airport. On that very short but formative visit, I remember three things about Rye: sidewalks, a store called Rags, and a park that leads to a beach that leads to the sea. The sidewalks stood out because I love going for long walks. My childhood in Pennsylvania lacked very little, but my town had few sidewalks. The sidewalks in Rye connected everyone in town in a way that was more small city than suburb. This is a place where people can travel on foot and where houses are close together, not a sprawling suburb with subdivisions of homes set on a half-acre or more. Maria and I walked on one of those sidewalks to arrive at the most adorable town center, Purchase Street.

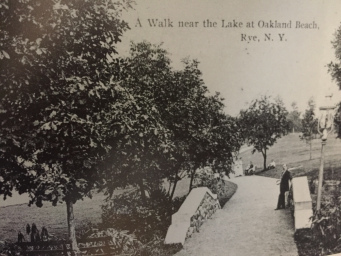

Maria’s tour of Rye was brief but left an impression, and the highlight of it was Rye Town Park. We didn’t even go into the park or see the beach, but as she drove from her neighborhood, where colonial homes sat on postage-stamp lots, over to Forest Avenue and along the town park, she casually commented, “That’s the park and the beach, and we ride our bikes there with friends.” Until that moment, I probably hadn’t looked at a map of Rye to know it was on the water. I peered out the window at the sidewalk, stone wall, rolling hills, brown grass turning to green, a small pond, and pavilions while I imagined the sand and sea beyond it. I wanted to ride my bike there with friends. Not a bad place to grow up, I thought.

We left before sunrise for Florida, and other than a graduation party and Maria’s wedding, I did not venture north of the five boroughs to visit Rye or this gem of a park until five years ago. Nearly twenty years and three kids later, having spent my entire adult life in New York City, we started to ask some What If questions. Those questions led us to Rye, and back to that park and beach from my rose-colored, youthful memory. Rye Town Park is one of the reasons we moved here. It is probably one of the reasons many people from the city move here. As with urban living, Rye offers neighbors an arm’s length away and public green spaces where people in the community can gather.

My family treasures the Rye Nature Center. Edith Read is truly a sanctuary, and we walk the trails and rocky beaches, watching the osprey fly overhead. One could spend the whole day exploring the Marshlands, watching the ecosystem change as the tides rise and recede. But it is Rye Town Park that fills me with that feeling of community, the place where triathletes train, dog lovers gather, families with children meet, brave swimmers plunge in cold water, friends whose children have grown and flown walk hand-in-hand with their spouse on the boardwalk, philanthropists raise awareness, and a cross-section of Rye weaves a web of spontaneity and joy.

The unique placement of this park, a green space on the waterfront, has always struck me as serendipitous. In a town where real estate is key, how did this park on the water come to be? After years of teaching students about my beloved Central Park and the lost Seneca Village, a community displaced to secure Olmstead and Vaux’s urban oasis, I started to wonder, how did Rye get so lucky? What was here before? The pavilions, bathhouses, boardwalk and Playland in the distance tell a piece of the story, but it turns out there is much, much more that we can no longer see, unless we look beyond the grass, sand and aging structures and turn back time. What if a few things had been different, and we did not have Rye Town Park?

At the end of Dearborn Avenue, one can stand and imagine a very different scene in the late 1800s. The land where the park stands was not a park at all. This land was owned by the Halsted family who owned the Knapp house, and in 1880, William B. Halsted built an inn at the end of Dearborn Avenue called Oakland. People started coming from near and far for day trips or vacations, many on the daily ferries that crossed the Sound from Oyster Bay, Long Island to Rye. Ferries quickly expanded their service to include New York City and towns along the water in Westchester and Connecticut.

View of Oakland Beach Showing Camps

With the increasing crowds, the Halsteds recognized a fantastic real estate opportunity. Around 1890, Augustus Halsted started allowing people to build summer bungalows on the property. He collected the rent for them, $60-$90 a season. Some local residents rented out their year-round homes in town to live in a bungalow for the summer. The Seventh New York Regiment had its own row of platform beach tents. This quickly grew into a village of over 200 bungalows bustling with residents and day trippers. J. Henry Halsted was the proprietor of the bungalow community in the early 1900s, and he installed lamps along the beach for evening swimming as well as bath houses and canoe rentals. With grocery stores, a pharmacy, hotels, restaurants and other amenities further down the beach in the Rye Beach area, a family could live at Oakland Beach all summer quite happily. A giant slide and waterfront snack bar added to the convenience and fun. In the heart of the action, the Westchester Beach Club built a clubhouse around the turn of the century on Dearborn Avenue with seven sleeping rooms, changing rooms and a large dining room and parlor for gatherings. The trolley line ran from town to the beach, making summer life on the water even more accessible.

Changes happened quickly from the time the first bungalow was built to when Rye Town Park became a reality, and fortunately, the stars aligned and our park gained a lasting foothold. Starting around the turn of the century, debates grew over how best to secure public access to Oakland Beach and whether the Village or the Town would maintain the public space. Opposing a public space were wealthy landowners who preferred a private sale of the Halsted land over a potentially noisy and crowded park. With mounting support for a park, George Slater of the Rye Town Counsel drew up a proposition to make Oakland Beach a Town park and on election day in 1907, all election districts in the Villages of Rye and Port Chester and the Town of Rye approved the proposition. In 1908, the State of New York authorized the Town of Rye to acquire the Halsted Property for Rye Town Park. Augustus Halsted received a fair price for his property and the bungalows were dismantled or in some cases, moved to other nearby locations to form new residential streets. Josiah Bulkley created Bulkley Manor by lining a dirt road with bungalows.

By 1909, the town had cleared the path for the park’s construction. In less than two years, the Town’s new team of architects and landscape designers built a lasting future for Rye Town Park. The architecture firm of Upjohn and Conable designed the buildings, and the landscape architecture firm of Brinley and Holbrook designed the park. Construction took place during 1909 and early 1910, with the park and beach opening in time for the 1910 summer season. While teams worked quickly and efficiently, the resulting construction is exceptional and enduring, part of what has given Rye Town Park a significant place among historic and architectural landmarks. The Spanish Revival or Mission style bathhouses and pavilions were the keystone of the Park’s design. This architecture, popular in California at the time, was part of the Craftsman aesthetic. It is reflected in some craftsman-style homes in neighborhoods surrounding the park, also built in the early 1900s.

The crowded bungalow village became a park of rolling hills and paths, with the signature duck pond in the middle. The view north from the pier on Dearborn was transformed by the dramatic towers and stucco walls of the pavilions and bath houses. Off in the distance, visible from the end of Dearborn Avenue and only a walk away, are the hotels and amusements of Rye Beach. In 1909, the ferry service began taking automobiles on board and became the first car ferry across the Long Island Sound.

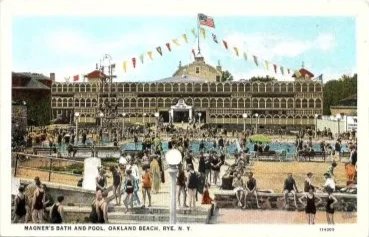

The park’s quiet paths gave some respite to the crowded waterfront, leading real estate investors to focus their efforts on Oakland Beach. In the 1920s, just south of Dearborn Avenue, J.P. Magner built his “Million Dollar Bath and Pool,” advertised as the biggest in the east. In addition to the pool, it had sport courts and a dance hall. Famous stunt actors Johnny Weismuller and Buster Crabbe led pool exercises and did tricks off the high dive. At first, Magner ran the pavilion just north of Dearborn Avenue as part of his complex. When he lost control of that, he built his own enormous pavilion. The complex was open from 1928-1966, and in 1970 Water’s Edge was built on what was Magner’s Million Dollar complex.

Tree Lighting Ceremony

With all this change, it feels almost miraculous that Rye Town Park and that short stretch of beach we call Oakland Beach, less than a half mile long, are today very much what their designers envisioned over a century ago. The towers and pavilions are in disrepair, and we continue to debate the best use of the space, best ways to maintain it, and best sources of revenue. Restaurants change hands. Ferries no longer run, a detail for which the residents on Dearborn Avenue are likely grateful. New visitors and residents arrive; new traditions take hold. This year, a family in town convinced enough people that the park needed a treelighting ceremony and holiday sing-along. Hundreds of us gathered with neighbors near the entrance at Forest and Rye Beach Avenue, sipping hot chocolate and singing with friends in the glow of a magical tree. In a balance of respect for history and openness to change, our little park along the beach has survived, and thrived, for more than 100 years. And Yes, I tell my eighteen-year-old self, this is not a bad place to grow up.

Sources include:

Postcard History Series: Rye by Paul D. Rheingold

Rye’s Waterfront Parks: Rye Town Park, Playland and their Neighborhoods, Walking Tour by Eugene McGuire

Original sources from the Rye Historical Society Archives